Stopped by a friend’s house a few days ago to do homework, which somehow devolved into me analyzing what programming language I should try to learn next in a corner, which is completely irrelevant to the rest of this post. Oops.

Anyway, in normal-math-curriculum-land, my classmates are now learning about matrices. How to add them, how to multiply them, how to calculate the determinant and stuff. Being a nice person, and feeling somewhat guilty for my grade stability despite the number of study hours I siphoned off to puzzles and the like, I was eager to help confront the monster. Said classmate basically asked me what they were for.

Well, what a hard question. But of course given the curriculum it’s the only interesting problem I think could be asked.

When I was hurrying through the high-school curriculum I remember having to learn the same thing and not having any idea what the heck was happening. Matrices appeared in that section as a messy, burdensome way to solve equations and never again, at least not in an interesting enough way to make me remember. I don’t have my precalc textbook, but a supplementary precalc book completely confirms my impressions and “matrix” doesn’t even appear in my calculus textbook index. They virtually failed to show up in olympiad training too. I learned that Po-Shen Loh knew how to kill a bunch of combinatorics problems with them (PDF), but not in the slightest how to do that myself.

Somewhere else, during what I’m guessing was random independent exploration, I happened upon the signed-permutation-rule (a.k.a. Leibniz formula) for evaluating determinants, which made a lot more sense for me and looked more beautiful and symmetric

\[\det(A) = \sum_{\sigma \in S_n} \text{sgn}(\sigma) \prod_{i=1}^n A_{i,\sigma_i}\]

and I was annoyed when both of my linear algebra textbooks defined it first with cofactor expansion. Even though they quickly proved you could expand along any row or column, and one also followed up with the permutation formula a few sections later, it still felt uglier to me. Yes, it’s impossible to understand that equation without knowledge of permutations and their signs, but I’m very much a permutations kind of guy. Sue me.

But this blog is not quite for that stuff, and it’s still too far from our topic; Algebra II does not care about determinants for matrices above \(4 \times 4\). All you need to do is learn (I’m sorry, memorize) Cramer’s rule (which I guess I must have learned back then but have utterly forgotten about until this month for the same reasons) and evaluate the formula for the area of a triangle with a \(3 \times 3\) determinant, when a \(2 \times 2\) determinant after calculating the actual displacement vectors would make much more geometric sense.

Well, of course normal math education has been like this — unmotivated, prescriptive, and most of all pathologically boring — for quite a long time, to the point where it seems the textbook writers need to mark the actual problems in their books with bold red-starred tags reading “Open-Ended Math”. And I don’t know much about fighting the system as a whole, but I guess the experience I’ve been rambling about have motivated me enough to write something about matrices. What follows is an attempt to answer all the questions and clear up all the confusion I remember my past self had so many years at this point, and, I’m hoping, help others too. I tried to make this brief, partially because I’m lazy and partially because I know most of the intended audience’s attentiveness would decrease exponentially as the length, starting with the usage of “exponentially” in this sentence. I don’t think I succeeded, so then I added crappy TL;DRs. Anyway, I expanded my own intuition a lot during the writing of this post, so even if nobody else reads, I won’t have wasted my time completely.

At the same time, keep in mind that this is not in the slightest a standalone intro to matrices. You will get a terrible impression of how matrices work if you don’t use a textbook or some other rigorous reference. There’s not much theory; I just want to explain why matrices look so weird when you first get into them.

The first question, coming just after we learn to add matrices, of course:

Why is matrix multiplication defined in such a complicated and weird way? Why can’t we just multiply corresponding elements like we did for matrix addition?

The first thing you should realize is that, even though you’ve only experienced multiplication as an operation on numbers (integers, rationals, reals, and so on), “multiplication” is somewhat of an indiscriminately-used buzzword in higher mathematics. In abstract algebra, we’re “multiplying” permutations, matrices, sets, endomorphisms, and more scary-sounding things; actually, most of the time we’re multiplying things without even knowing what they are, or caring that we don’t know what they are. So in the big picture, this definition of matrix multiplication is not strange at all.

Well, why not just multiply corresponding elements? Sure you could, and it would be a rather nice definition*. Unfortunately it would be neither very interesting nor very useful, because each of the elements would only ever be able to interact with elements in the exact same place. You might as well just take the numbers out of the box and multiply them one by one.

It just happens, really, that the way matrix multiplication is defined is a very interesting one. More on this below.

TL;DR: You can if you want, but it’s boring. The interestingness of the actual definition is well worth the complexity.

- technical blabbering: when combined with normal matrix addition, element-by-element matrix multiplication would make the set of matrices of some fixed dimension into a commutative ring with unity. However, this structure would be trivially isomorphic with the direct product of a bunch of copies of \(\langle \mathbb{Z}, +, \cdot \rangle\). Yeah, boring.

Okay, why then are we taking rows from one matrix and columns from the other? Why can’t we just agree to use all rows?

To explain this well, I think I have to explain what matrices often mean to mathematicians beyond a bunch of numbers.

Quite often in linear algebra, we pretend an \(m \times n\) matrix is a linear mapping from \(\mathbb{R}^n\) to \(\mathbb{R}^m\). In English, this means that a matrix is a certain rule that turns a list of n numbers into a list of m numbers that is linear.

To even better visualize, you can think of a matrix as a machine in a factory with an “out-pipe” that always spits out lists of m numbers, and an “in-pipe” that only allows lists of n numbers. If you put a list with more numbers or less numbers into the in-pipe, the machine would explode, reducing factory efficiency and creating an unjust externalized cost in the manufacturing pipelines. Something like that. That’s why you can’t multiply matrices of random sizes: the machines won’t fit together.

The normal way matrices are drawn are, I think, quite misleading in this regard, because it makes matching rows of one matrix to columns of another seem completely nonsensical. But if you matched rows to rows, that would be like connecting the out-pipes of two machines to each other, leaving two in-pipes protruding. You can’t build a big assembly line that way without getting all confuzzled by which end joins with which end at every connection. If you imagine hanging each matrix by its upper-left corner, you get an alternative visualization that may seem more reasonable:

edited 2015/01/03 after feedback; darn, typing is hard

Man, I can’t believe I had to come up with this visualization myself. This deserves to be in every textbook mentioning matrices ever. You even get to memorize the order in which to write matrix dimensions for free, something I realized in the writing of this post that I still don’t have down perfectly.

*TL;DR: I don’t have a satisfying way to answer this briefly, but it’s like when you’re assembling Lego, you connect the bumpy side of one brick to the holey side of another. This way, after the connection, the combined brick still has one bumpy side and one holey side. Now imagine rows are bumpy and columns are holey.

…weeeeelll, told you it wasn’t satisfying.*

You can’t just put linear in italics and tell us to forget about it. That’s not fair.

If V and V’ are vector spaces over the field K, a linear mapping is a mapping F: V → V’ which satisfies the following two properties:

- For any elements u, v in V, we have F(u + v) = F(u) + F(v).

- For all c in K and v in V we have F(cv) = cF(v).

TL;DR: Never mind.

Seriously?

Okay, okay, here’s a crude English example.

On Monday, Bob the mathematician is going to bake 1 cake and 20 muffins. Because Bob is a mathematician, he doesn’t like the words “cake” and “muffin”; they’re too long and he might spell them wrong. So, he decides to call cakes “food item 1” and muffins “food item 2”, and creates a baking plan vector that looks like this. (If you’re wondering whether he’s bonkers or just mean for writing them vertically, be patient and wait for the next question.)

\[\left[ \begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 20 \end{array} \right]\]

(Did you learn to imagine “vectors” as arrows in space? That visualization has its merits and will probably get you through high school, but it doesn’t work so well generally if you try to put complex numbers or elements of the field \(\mathbb{F}_2\) in them. You may want to try imagining them as lists of numbers. For now.)

Now, Bob has a rule for calculating, based on the numbers of cakes and muffins, how many bags of flour (“ingredient 1” according to him) and how many eggs (“ingredient 2”) he has to buy. Maybe he’ll need 3 bags of flour and 5 eggs. His rule has these two properties:

- Suppose Mary wants to bake 2 cakes and 6 muffins, and calculates she needs 4 bags of flour and 3 eggs. But then Bob happily learns that Mary is also interested in baking — they even calculate their ingredient lists by the same rule, no, the same linear rule — and not being a very normal mathematician, decides to ask her over to his house. They agree to help each other bake, and to be even nicer, Bob decides he’ll buy the ingredients for both of them. Now Bob needs to figure out how many ingredients he needs for 1 + 2 cakes and 20 + 6 muffins. But he doesn’t need to use his rule again; he just has to add their ingredient lists together directly, and he goes happily off to buy 3 + 4 bags of flour and 5 + 3 eggs.

- The next day, Bob decides he wants 3 cakes and 60 muffins. Since this is just 3x what he wanted on Monday, he will just need 3x as many of each type of ingredient, i.e. 3x3 = 9 bags of flour and 3x5 = 15 eggs.

Any rule like Bob’s with these two properties is “linear” (with a lot of simplification, e.g. Bob must master the dark art of making negative cakes.)

TL;DR: No.

Wait, why is Bob writing vectors as numbers vertically in a column? That doesn’t make any sense. Writing them in a row is so much more reasonable.

The slightly unfortunate convention in algebra is that vectors are normally column vectors, i.e. matrices with everything in one column. In fact, as I was officially warming up to linear algebra, one of the first intuitive things I realized was that it was almost always a better idea to imagine that matrices were made of a bunch of columns written left-to-right, instead of a bunch of rows stacked top-to-bottom. This is unfortunate of course because it goes against the way we’ve been taught to read: left-to-right for the first line, then the second line, and so on.

If mathematicians transposed all their matrices as well as the multiplication convention, or simply decided to write functions to the right of their arguments, math could perfectly well have been developed with normal vectors being single-row matrices. Reading matrices would be more intuitive, and typesetting vectors would be easier. So, why not? A little searching online doesn’t give me any good reasons, so I’ll just give the best guess I have: the column convention allows coefficient matrices of systems of equations to have their elements be arranged just like the coefficients in the systems of equations written out the normal way in full. I think it could have gone either way, honestly.

TL;DR: Electrons are negative and October is the tenth zarking month. Deal with it.

Well, okay, a matrix represents a linear transformation, but which? What do the actual numbers in the matrix mean?

It’s actually pretty straightforward if you remember to imagine a matrix as a bunch of columns. Continuing the random story of Bob, column 1 (corresponding to food item 1) just lists how many bags of flour (ingredient 1) and how many eggs (ingredient 2), in that order, are needed for one of food item 1, and column 2 lists how many bags of flour and how many eggs are needed for one of food item 2. It’s just what Bob would get after writing out each of his individual recipes in the weird vertical manner and sticking them together.

TL;DR: Each column indicates what each input number turns into. You didn’t really need this TL;DR for such a short answer, did you? I sincerely hope not.

Okay, I think I’m ready to fall asleep now. Can I have some background on determinants and Cramer’s rule and all that before we get there?

If we’re working with just linear transformations without any reference to geometry, you get one big piece of information from whether a determinant is zero. If it’s not zero, that means that just by looking at Bob’s ingredient list, you can determine how many cakes and muffins he made. Or, with the machine analogy, you can always build a reverse machine to a machine whose determinant is nonzero. If you connect the two machines, you’ll get a combination that takes a list of numbers, wastes a lot of time calculating things, and then gives you the exact same list — in short, an entirely useless machine. The reversing machine is called the inverse matrix of the original one. Once you multiply them, the matrix you get, the one that does nothing at all, is called the identity matrix. I don’t remember if this is in your textbook, and in any case it’s only terminology, so don’t agonize over it.

On the other hand if the determinant is zero, then you can’t always do that. In fact, if the determinant is zero, Bob can make a food list other than the “all-zero list”, possibly involving negative or imaginary cakes, that in total uses no ingredients at all.

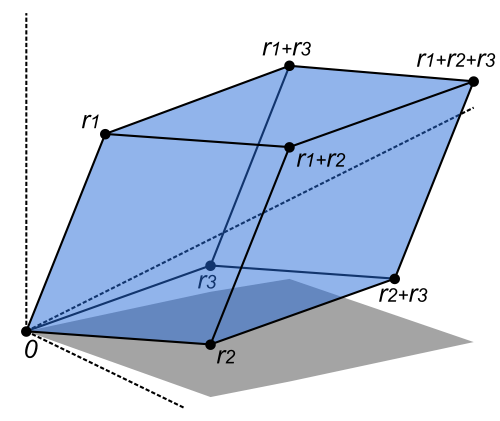

But only noticing if the determinant is zero or not is boring, so let’s jump back to the geometry for a while. As long as we’re working with real vectors (ones you can imagine as arrows; okay, I lied, go back to imagining them that way for a while), there’s a simple geometric way to imagine them. Copy the vectors a bunch of times and compute the volume of the result. That’s the determinant (give or take a minus sign)! It still works approximately like this for higher dimensions, even though you probably will have lots of trouble visualizing them.

Or so the joke goes:

Engineer: “How could you possibly visualize something that occurs in 14-dimensional space?” Mathematician: “It’s easy! You just have to visualize it in N-dimensional space and let N go to 14.”

As for Cramer’s rule, I confess that the math is straightforward once you write it out, but I haven’t the faintest idea how to explain it intuitively. It’s somewhat analogous to comparing two parallelograms with the same base. Perhaps Wikipedia’s geometric interpretation will help.

TL;DR: The determinant expresses the hypervolume of the hyperparallelogram bounded by the vectors. Cramer’s rule follows quickly from comparing hyperparallelograms. “Hyper” is a crappy prefix for geometry in N-dimensional space; set N = 14, or just 3 to match the picture, if you want.

Alright, that’s enough barely understandable information for me today; just remind me again, why are we studying this?

To be honest? I have no idea.

From what I’m studying now, I have no doubt that the world of matrices and all the linear algebra it’s linked to is a very beautiful world (and full of so many applications too, for the practical-minded!) But I also must admit that I have no idea how anybody could expect one textbook chapter to bring this out. I thought matrices were boring as nails when I first learned them, and I still cannot see how I could have had any other opinion based on the curriculum. I think if I were to write an algebra book for normal people I’d leave matrices out of the book altogether.

So I won’t sugarcoat it: I’m studying it because it’s interesting, and I don’t know why people expect everybody else to. Maybe you’d be interested if it were explained better — all of the math from first grade, not just this measly chapter on matrices. I could complain a lot more, but it’s not like I could ever beat just linking to Lockhart’s Lament (PDF). To everybody who’s confused out there by this stuff: I’m sorry, and I hope I helped.